The (possibly) Impressionist Garden of Claude Monet

For four centuries the art of gardens in France was dominated by the classical trend, and then, for about a century, by what is known as the landscape and mixed trends. On the threshold of the 20th century, garden designers needed to turn towards a new trend, an evolution which was at first slight and then increasingly shared, and which embraced many modern artistic movements. Towards the end of the 19th century, a revolution shook the world of art, and this had repercussions on the world of the garden. It is difficult to date the beginning of this new awareness, and historians often take 1874 as the starting point, the year of the inauguration of the exhibition in which some of the artists who had been rejected by the official Salon, for those who still followed academic canons, participated. Among these, the figure that interests us most is Claude Monet, one of the founders of the movement that would later be called Impressionism.

The iris garden, Claude Monet, 1900

Nowadays, in the context of modern art, the more traditionalist critics consider Impressionism to be the last movement that produced “art in the true sense of the word”, but obviously for the time it was a real reversal in the way of seeing, creating and conceiving a work of pictorial art. It is based mainly on the constant analysis of light, on its changes at every moment of the day (the artists, and Monet himself, often repeated the same subject several times at different times, to record the variations), capturing the sensations of a fleeting moment, the impressions, rendering them on canvas with pressing, irregular, even sketchy brushstrokes, and often painting en plein air. All this contrasted with any dictates of the School of Classical Arts, but by then the revolution had taken hold and nothing could stop it. Modern art was born, and we can more or less cover the period from the 1860s to the 1870s. The fact that the work of art was not only to be admired, but that the predominant aspect was that of perception, led artists to re-evaluate the way in which nature was observed, and Monet, among others, became aware of the link between art and nature, or between art and landscape.

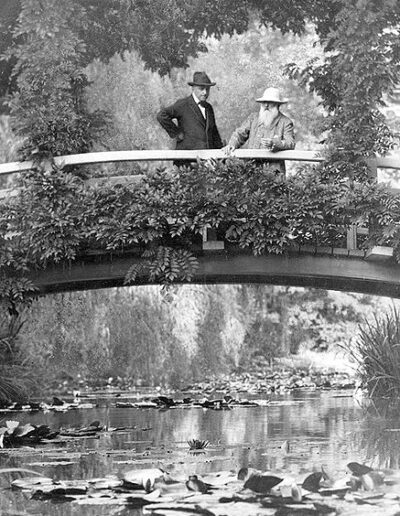

Claude Monet and his wife Alice on the Japanese bridge at their estate in Giverny, before the creation of the garden

His desire to capture every aspect of the landscape led him to design and then build a work of art on several occasions, marking the beginning of a new artistic and gardening career, but one that needs to be clearly defined to avoid often unfounded misunderstandings: the Giverny gardens. These were created in the small town of the same name in Normandy, to meet the artist’s pictorial needs: Monet did not leave it to Alice – his wife – to design a garden for leisure, he knew exactly what flowers and colours he wanted, he subordinated everything to his work. Soon, the large trees shading the facade were removed. Everything was planted so that he could paint, finding in this nature that he composed the necessary elements for his canvases.

Plan of the gardens of Claude and Alice Monet's house in Giverny

What we see of the garden today, however, is the result of restorations based both on the maps and photographs of the period and on Monet’s spirit, imbued in his many paintings, and so it has undergone an influence that perhaps it did not possess in the past. We can speak of an Impressionist garden, certainly, but not in its entirety. Its design consists of three parts: one near the house with elongated or rounded flowerbeds and a few trees, and two others resulting from the layout of the avenue in an almost central position.

Claude Monet in the central avenue in front of his house

The east side has rectangular flowerbeds housing vertical trellises for climbing plants, while the west side is organised with an English-style parterre. Monet wanted his garden to be balanced like a palette. He cut regular rectangles in the Clos Normand, each of which has a colour. The result is never tiring because this palette transforms. It certainly evolves during the course of the year, according to the calendar of blooms, but also according to the light of day. Walking along the paths, everyone can indulge in a visual experience that is different on each visit: the colours mix, the perspective of the masses blurs the geometry of the path and, depending on the height of the plants, unexpected harmonies of colour are composed and erased. Certainly this description does not suggest a garden associated with the Impressionist movement, but rather a formal garden, which has learned the lesson of its illustrious predecessors.

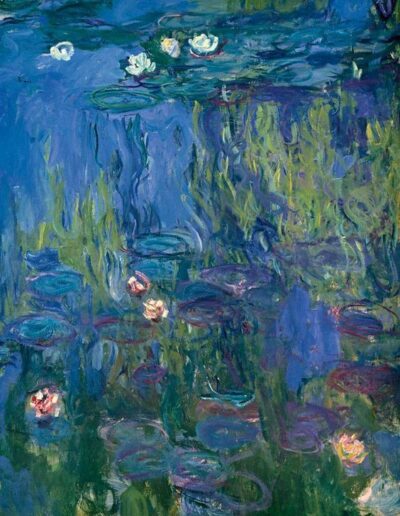

Where, then, is this display of Impressionism, this cult of light and nature that excites and provokes strong feelings in the artist’s soul? The answer lies in the only part that is not land or trees, but water: the famous water lily pond, as much loved by the artist as it is painted and studied in its pure simplicity.

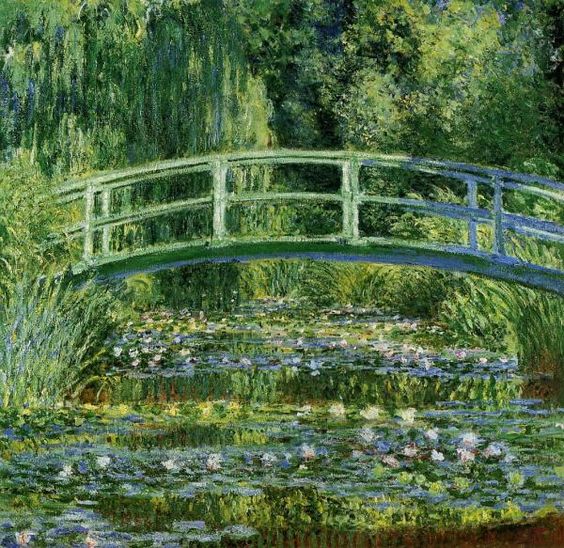

View of the Japanese bridge over the water lily pond

It is a rectangular basin, where white and pink water lilies, irises and other aquatic essences grow, with the banks surrounded by poplars and weeping willows, where paths lead to a small bridge (also portrayed many times), reminiscent of the Japanese tradition that Monet often studied and which profoundly influenced his work.

It is here that we find the truly artistic component of the project, that link which unites the useful (a comfortable place to paint in peace and away from the rest of the world) and the enjoyable (shadows and light, reflections on the water, movements generated by the wind or the flickering of the sun’s rays through the treetops).

White water lilies, Claude Monet, 1899

On this subject, Georges Clemenceau commented in 1928: “Monet’s garden is ascribable to his work, realising the fascination of an adaptation of nature to the painter’s work and light. An extension of his atelier outside, with palettes of colours profusely scattered everywhere for ocular gymnastics, through the appetites of vibrations that await a fevered retina with unfulfilled joy. There is no need to know how he created his garden. What is certain is that he did it as his eye commanded him to do later, at the invitation of each day, for the satisfaction of his chromatic appetites”.

The Japanese bridge

Sensations, tranquillity, reflection, all come together in this dreamlike atmosphere which once again brings to mind ukiyo-e, images of the floating world of Japanese culture. But as previously mentioned, what we are experiencing today is a reinterpretation of that dream, in fact the garden we see today is necessarily different, it no longer belongs to a man, but is the image of his celebration, the representation of a hypothesis or “how Monet would have wanted his garden today”, which seeks to interpret the spirit of the master and stages it, with the aim of transporting the visitor into the enchantment of the atmospheres of the Impressionists, dazzling him in an astonishing excess of blooms.

But that is precisely where its strength lies, in its everlasting bond with art that transcends time and successive transformations, giving us a spectacular example of the bond that would permeate garden art from then on. Giverny is a singular case in which the artist and man overlap with the paintings and the garden: the former are eternal and can be handed down, the latter is ephemeral and subject to the whims of time. Almost a paradigm of the very essence of Monet’s art, which is difficult to translate into a scientific logic and even more so into the everyday care of a garden.